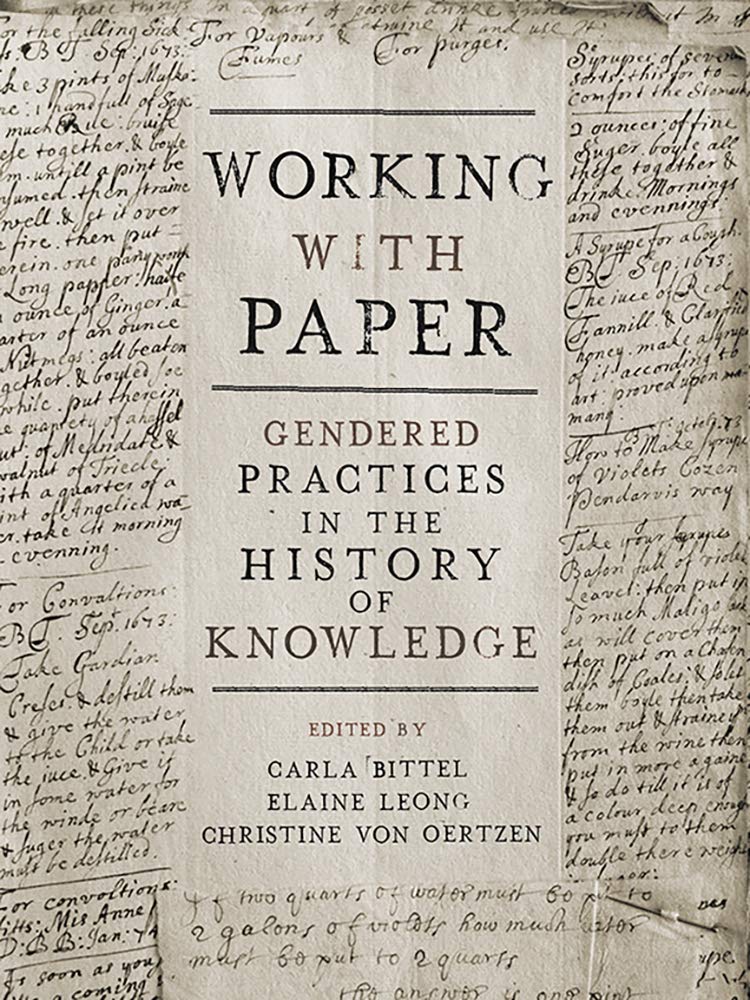

Working with Paper Gendered Practices in the History of Knowledge 1st Edition by Carla Bittel Pickering, Elaine Leong, Christine von Oertzen 0822945592 978-0822945598

$50.00 Original price was: $50.00.$25.00Current price is: $25.00.

Working with Paper Gendered Practices in the History of Knowledge 1st Edition by Carla Bittel Pickering, Elaine Leong, Christine von Oertzen – Ebook PDF Instant Download/Delivery: 0822945592, 978-0822945598

Full download Working with Paper Gendered Practices in the History of Knowledge 1st Edition after payment

Product details:

ISBN 10: 0822945592

ISBN 13: 978-0822945598

Author: Carla Bittel Pickering, Elaine Leong, Christine von Oertzen

Working with Paper Gendered Practices in the History of Knowledge 1st Table of contents:

PART I Beyond the Page : The Sociomaterial History of Paper

ONE Letter Writing and Paper Connoisseurship in Elite Households in Early Modern England

Writing a letter requires a series of small but consequential decisions based on two baseline questions: What is my relationship to the recipient of my letter? What do I hope to achieve by writing it? The answers to these questions dictate the style, content, and materiality of a letter. In the early modern period in particular, material aspects such as the quality and size of paper, the style of handwriting, and the way in which a letter was folded and sealed were significant indicators of the sender’s intent, reflecting a complex and unwritten set of sociomaterial practices communicated by example…

TWO Papering the Household: Paper, Recipes, and Everyday Technologies in Early Modern England

Across early modern Europe, the household—as a domestic space and as a collective of historical actors—played a crucial role in a range of medical activities. In many cases of ill health, it was the first port of call.¹ Household collectives often worked together to diagnose sickness and ailments, nurse and care for the sick, source and produce drugs, and promote general health maintenance through diet and exercise.² To accomplish this work, they utilized a broad knowledge base, a range of material objects, and a number of complex processes. Many recorded their practical knowledge in the form of recipes

THREE The Sociomateriality of Waste and Scrap Paper in Eighteenth-Century England

An intense focus in recent years on the history of the book, publishing, and journals has done much to reveal the role of paper as a technology of writing and text.¹ Undoubtedly this was one of the principal uses of paper in the early modern period. But as this chapter will argue, paper served many other uses and, at least in the English case, it was exactly the adaptability and serviceability of paper, the fact that it was not just a carrier of text, that may have given it such value for early moderns. Paper was exemplary of the kind…

FOUR Paper Trials, Multiple Masculinities, and the Oeconomy of Honor

In 1765 the Protestant pastor Jacob Christian Schäffer (1718–1790) published the first in a series of six books recounting his paper trials.¹ Versuche und Muster ohne alle Lumpen … Papier zu Machen opens by describing his reasons for undertaking such trials, which sought a material substitute for the linen rags that were used to make paper. If we are to believe Schäffer, his chief motivation was to resolve the paper crisis at the time.² He was particularly concerned about how difficult it had become to procure the kind of fine white writing paper that was used to publish learned…

PART II Transcending Boundaries Tools and Technologies

FIVE Bookkeeping for Caring: Notebooks, Parchment Slips, and Enlightened Medical Arithmetic in Madrid’s Foundling House

On March 29, 1801, Juliana de Baza bundled up her five-month-old niece, María Salome, and left her home in the center of Madrid. She walked down the bustling La Montera Street and headed for the nearby foundling house, where she left her brother’s baby.¹ Just as soon as the nun at the door received the baby, the paper machinery of the house swung into action.² In the chilly office that never closed, by the light of an oil lamp, the clerk perused the letter that had accompanied María Salomé, searching for confirmation and evidence that the child had been baptized.³…

SIX Unpacking the Phrenological Toolkit: Knowledge and Identity in Antebellum America

Opening Orson and Lorenzo Fowler’s 1850 edition of the Illustrated Self-Instructor, one comes face to face with phrenology (fig. 6.1). There, a large, ambiguously gendered head invites readers to see a version of themselves on paper. A profile is mapped into multiple sections, each section containing an illustration of a localized character faculty, or “organ,” of the brain. These “symbolical heads,” could look masculine, with strong jaws and large foreheads, but the same one could also look feminine, with pronounced eyelashes, rosy cheeks, and pink lips. Coupled with a chart of measurements, completed by a phrenologist, the text served as…

SEVEN Keeping Prussia’s House in Order: Census Cards, Housewifery, and the State’s Data Compilation

In 1871 the Prussian census bureau introduced a new paper tool, the so-called individual counting card. Central to Prussia’s ambitious and far-reaching census reform, the small form was robust and mobile. It was designed to speed up the compilation effort and facilitate statistical complexity, serving at once as a recording and a sorting and counting device.¹ Counting cards consisted of simple-sized heavy-duty paper, cut to twenty-one centimeters in length and twelve centimeters in width.² Providing just enough space to record all required enumeration data for one person on a single page, each card weighed merely 7.5 grams—but together, the…

EIGHT Tracing Paper, the Posture Sciences, and the Mapping of the Female Body

At the turn of the twentieth century, experts in the social and medical sciences worried about rising rates of defective human posture in the United States. Some studies estimated that as many as 80 percent of Americans demonstrated faulty form.¹ In the view of these experts who believed that good organ function and character depended on upright carriage, slouching bodies threatened to bring about an increase in infectious diseases and an overall decline in the physical and mental fitness of the nation. By the turn of the twentieth century, standardized posture assessments became a defining feature of the burgeoning practice…

COLOR PLATES

PART III Knowledge, Power, and the Everyday

NINE A Letter Is a Paper House: Home, Family, and Natural Knowledge

When the naturalist and cleric John Ray died in his home in Black Notley, Essex, in January 1705, his widow, Margaret Ray, would have washed his body and dressed it in a woolen shift, perhaps with a bit of black embroidery at cuff and collar. She tied the shift at the feet and then wrapped the corpse in a woolen winding sheet (not linen, as required by a parliamentary statute that bolstered the English woolen industry and reserved linen for papermaking).¹ John’s body, by his own request, was nailed into a plain wooden coffin so that his corpse could not…

TEN Family Notebooks, Mnemotechnics, and the Rational Education of Margaret Monro

Sometime in 1738 the eleven-year-old Margaret Monro (1727–1802) received a letter from her father. Though she spent most of her early years at home, she was most likely attending a boarding school located outside Edinburgh in the Lowlands of Scotland at this time. Written in a congenial and familiar manner, her father’s letter outlined a plan that, if executed diligently, would improve her reason, advance her virtue, and garner the highest esteem from her acquaintances and relations. The plan was to send her a series of letters on female conduct that explained how to make rational decisions in a…

ELEVEN Papier-Mâché Anatomical Models: The Making of Reform and Empire in Nineteenth-Century France and Beyond

Sexuality and reproduction have long been central features of anatomical models and representations in two and three dimensions. Early modern models in wood and ivory presented pairs of male and female bodies side-by-side. Pregnancy, in particular, was a frequent subject: the flap anatomies of early modern Europe featured pregnant women, as did most wooden and waxen models of female bodies. Scholars have paid much attention to the gendered aspects of these objects, and have argued that they have often played key roles in articulating and affirming culturally and historically specific gender roles, despite their supposed allegiance to an objective, timeless…

TWELVE Women Who Worked with Documents to Rationalize Reproduction

In the spring of 2016 three students joined me in a project building paper population models for 1930s America. My “history lab” holed up in an art studio, plundering a razor to cut our large slabs of paper board, as well as washers, bolts, and colored pencils—the various stores of each pointed out by a fellow faculty member. Abby Balfour, Erin Burke, and Christy Mills—my students—worked out a method for drawing a reliable circle and took turns hacking out the discs.¹ Then they set about drawing and shading in with rainbow colors the hundreds of sectors required…

AFTERWORD Making and Using Paper in Late Imperial China: Comparative Reflections on Working and Knowing beyond the Page

In 1839 the papermakers of Macun and Zhongxing (Jiajiang County, Sichuan) sued the papermakers’ association of neighboring Yingjiang town. The details of the case are murky: a few years earlier, the Yingjiang association had commissioned a statue of Cai Lun, the Han dynasty court eunuch who invented paper and is worshipped to this day as the protector of the papermaking trade. Every autumn, Yingjiang papermakers carried the Cai Lun statue through the villages of Jiajiang’s paper districts and held a banquet in a temple, asking for Cai Lun’s blessing. Yingjiang papermakers claimed that possession of the statue gave them ritual…

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

People also search for Working with Paper Gendered Practices in the History of Knowledge 1st

how do gender roles affect the workplace

working with paper

working paper vs white paper

gendered job segregation

Tags:

Carla Bittel Pickering,Elaine Leong,Christine von Oertzen,Paper Gendered Practices,History of Knowledge

You may also like…

Psychology - Neuropsychology

Working with the Brain in Psychology 1st Edition Lynn A. Schaefer

Uncategorized

History - Islamic History

Psychology - Clinical Psychology

Reference - Genealogy & Family History

Psychology - Neuropsychology

Psychology - Clinical Psychology